|

To really understand how incompetent some people are when it comes to reporting incidents, you need only look at my old school. Wait, no… not the one of which you’re thinking! Let’s go back further to when I was in a Government high school myself.

It was the 90s, an almost lost decade when the great fashion styles of the 80s were now dead and replaced with slightly more conservative hair cuts and mobile phones that came in a bag. Yes that’s right, A mobile didn’t fit in your pocket. It came in its own bag. They were enormous! I remember that everyone thought that people who carried their own bag phone around, must have been either super important, or a complete tosser! In reality, it was the latter, but I digress. Whilst I prefer not to talk about my high school experience, because it could lead to far too many expletives being used in every sentence, the remarkable thing about life is the fact that we can learn some great lessons from complete idiots. Just take a look at the Darwin Awards, which is a great testament to this fact. Sadly, I don’t have another contender for the Darwin Awards on this occasion. However, there’s no shortage of idiots involved, so for those of you involved in risk management, this is what not to do when your school bus gets hit by a semi-trailer. Now it wouldn’t be fair to talk about the day trip to Narrabri without putting it into some sort of context. Why were we travelling two hours from Tamworth in Northern NSW to Narrabri just to have an argument? For me, this was one of the most exciting days of the year. It was the regional debating championships and for one, it had me out of school for the day, which was always preferable. More importantly, it was one of the best debating competitions around. Sadly, the English staff who were supposedly running debating, didn’t share this view. Since it wasn’t Rugby League, the rest of the school had a dim view of it as well. The only time I’d actually been to Narrabri for the championship was two years before when I was in Year 7 and we did very well, getting into the finals but coming runner up at the end of the day. The next year however, one of the students slept in, and so rather than leaving one student behind, the stupid teacher waited and did nothing for an hour and a half, until the student got on the bus. We arrived massively late and forfeited every single debate. Yet another stellar moment for the English Department. However, I’ll leave it at the fact that the English Department and I did not get along. There was some unpleasantness. I remember in Year 12, I was excluded from the debating team for apparently being too argumentative… but that’s a much longer story for another time! Back to the matter at hand. I was thrilled to be heading off to Narrabri for the day of debating. It was a knock out impromptu debating competition, which I loved and given the previous year’s mess, I was eagerly anticipating getting there and at least competing in the first round! Despite the fact that it had been raining overnight and drizzling that morning, all was going well. I was picked up on time in town, which was a pleasant surprise. Jumping on the bus, I found a seat right in the middle of the mini-bus on the driver’s side. It was on the outskirts of Tamworth when I first noticed the bus seemed to be all over the road. It was raining more heavily and the driver, one of the illustrious English teachers, had managed to slip the bus off the road twice into the soft verge at the side of the bitumen. On the second slip I banged my knee hard into the seat in front of me. “What an idiot,” I thought. (I was thinking worse than idiot… but I’m keeping this PG). This year we were in no hurry, but the teacher seemed hell-bent on racing the whole way there. Another twenty minutes on and with a few more bumpy shunts all over the road, we were close to Gunnedah and approaching a narrow bridge over the Mooki River. It was raining. We seemed to be speeding in a bus that had already slipped off the road a number of times and now were approaching the narrow wooden Mooki Bridge. I glanced up to see a semi-trailer heading in our direction. It was half way over the bridge. Then everything suddenly slowed down. I don’t remember hearing the screech of the wheels, but at some point the teacher had slammed on the brakes, the wheels had locked up and the bus spun around in slow motion 90 degrees. We were now sliding sideways straight along the road, completely out of control. Out my window, a massive bull-bar- covered grill was coming straight for me. Nothing profound was going through my mind as I grabbed to push my back hard into my seat and braced myself against the seat in front. There were no seat belts and we were about to be T- boned in the middle of the bus. It was the quick thinking of the truck driver who saved us that day. As I watched helplessly from my seat, the massive bull-bar came closer and closer. Suddenly the rig of the semi-trailer veered sharply left. It’s wheels shifted and rumbled off the side of the road. The driver was now trying to turn hard left and the bull bar was facing slightly away from me, but with the truck close to us now and with nowhere left to go, I held my breath. The bus was deathly silent. The most frightful, deafening sound of crunching metal smashed the silence. The semi had clipped the rear of the mini bus. The side windows shattered. Glass sprayed slowly through the air like a thousand diamonds hovering slightly, as the bus spun violently, before arcing to the floor. Glancing back, I saw the semi-trailer roll onto its side and into a ditch next to the road. We came to an abrupt stop. I sat there stunned as everything seemed to return back to normal speed. “I’ve got to get off the bus,” I thought. “What if it explodes?” With my ears ringing, I could now hear screaming and shouting throughout the bus. All I could think of was what if another truck comes along and hits us? I scrambled off the bus. It sat awkwardly, still halfway across the road. The massive semi-trailer lay motionless. Despite our teacher being a massive tosser, unfortunately he didn’t have an enormous bag phone, so we had to call emergency services 90s style!! I ran across the old narrow wooden bridge to the other side. Sure enough, another truck was picking up speed as it headed out of town. Standing in the middle of the road I flagged him down. I can’t remember what I said, or even if it made any sense, but with wreckage strewn all over the road ahead, it was fairly obvious we needed help. The truck driver got on the CB radio and soon we could hear the sounds and see the flashing lights of the ambulance and police racing towards us. A couple of students were still on the bus. The teacher had run off to the other vehicle and not bothered to check on any of us, despite the common sense rule of check your students! Given the fact he should have owned a bag phone, this wasn’t surprising in any way. As in every movie climax after the life or death conflict has been resolved, the flashing lights and uniforms around us seemed to create a sense of calm. I think I was too stunned and possibly concussed at this point to really be feeling anything. Although, I remember thinking, “We’re going to be late for the debate again!” A couple of students and the truck driver, who in his superb efforts to save us had broken his leg, were loaded into ambulances and rushed off to hospital. We were loaded back on the bus which still could be moved and driven to hospital. To say I was reluctant to board the bus was an understatement, especially with that guy at the wheel, who in my opinion was completely responsible for everything that had just happened. However, the police determined the bus could be driven only about 4 km to Gunnedah Hospital. We sat around and waited to be seen in hospital. One after another, a doctor checked us. My knee was sore and I felt exhausted. Otherwise, I was fine. For us, the ordeal was pretty much over, but for everyone else it had only just begun! Thanks to modern forms of communication at that time (the CB radio), which could be easily listened into by anyone, the 8.30am local ABC radio news had already broadcast the accident informing all the northwest that “a bus from a Tamworth school had crashed.” Panic arose for some primary school parents whose children had left that morning for Canberra. The 9am news stated, “The bus was not from Oxley Vale School.” The phones at our school, those ones that plug into the wall, went into meltdown, as only a tiny bit of information was released on the radio. By 11am, the school was named. It didn’t say that it was the debating team, a significant point by which most parents would have known it didn’t involve their son. Everyone, however, had assumed it was a football team or some other excursion and thus many parents were trying to ring one phone number all at once. The parents with children in the debating team had also found out and couldn’t contact the school due to the phones being engaged. If there’s one thing you should do in the event of a critical incident, it’s inform the parents of those involved as soon as you can! Release a detailed statement to the rest of the school community based on clear facts and in line with the needs of the community. Failing to do so, creates more problems. It creates panic and uncertainty and parents will fill in all the blanks you’ve left for them with their imagination. Soon parent imagination can turn into pseudo facts and you will have an even bigger mess on your hands. It’s hard to respond to that and much harder from which to recover. Rather than using another phone line to call the parents of the students who were involved, the school did nothing. Yes, that’s right! Nothing at all! The hopeless response to this major incident is probably one of the reasons why I believe risk and incident management is so important. Seeing people do something so badly, usually prompts me to do the opposite and make sure it’s done properly. A teacher at the school told my older brothers and gave them the tiny bit of information that was heard on the radio. One brother rang our mother at her work with the words, “The bus has crashed, but David is all right.” She in turn rang our father at his work and he kept dialling the school number to see if he should drive to Gunnedah or where. The school sent a teacher in another bus to come and pick everyone up from Gunnedah Hospital. There wasn’t anything wrong with this in itself. We were collected at the hospital, driven back to Tamworth and dropped off either at or near home or at a parent’s work with no meet and greet to the parents, nor any sort of handover. I was the only student with immediate parent contact. One boy was set down in town and had to wait about three hours for his regular school bus to take him home to Manilla. A number of students were dropped off at empty houses. After almost being killed in a horrible collision with a truck, the teacher somehow thought that dropping shaken teenagers off at an empty house was an appropriate thing to do! Even the most useless and incompetent teacher should have known better than that! Perhaps the teacher who picked us up should have been carrying two bag phones. As he was head of welfare for the school, it’s rather ironic that he appeared to know nothing about student welfare, but again that’s my opinion and a much longer story for another time in regards to what I believe was his incompetence and inability to fulfil an important role. The idea that it was ok to drop students off at home when nobody was there after a traumatic road collision was stupid even for the 1990s. I remember being dropped off at Tamworth West Primary School where my mother was teaching her Year 4 class. I wandered in, still possibly concussed and remember lying down somewhere in the classroom and falling asleep. Mum sensibly refused to take me home in her lunch break. What should have happened? All students should have been driven back to school. No one should have been left alone. Day boys could have been left under Matron’s watchful eye, until their parents arrived to collect them. Boarders could have been supervised by Matron and/or their dormitory master. From an incident response and management point of view, the lack of communication was pathetic. It might have been a lack of training, a lack of response planning, or just the fact that I went to a school that appeared to be run ineffectively. The bottom line was that there was no plan in place if something went wrong. It was evident that everyone was simply making things up as they went. Whilst critical incidents are fluid in nature and you may need to respond in an inter-active way to contain the initial situation, there is absolutely no reason why any school or organisation can’t have clear actionable steps in place to be able to respond quickly and effectively to a major incident. It’s vital that you inform parents and if needed, draw on resources in the wider community, such as local radio. Over the past 25 years, at no time did anyone from the school contact my parents to let them know what happened! At no point was the incident ever debriefed! At no point did anyone ask about the debating! Two years in a row, we’d forfeited the most awesome competition in the region and to this date, the school still hasn’t officially told anyone that the bus crash actually occurred. The Principal suddenly left the school and the questions about the crash, that parents asked at the P & C meeting, were unanswered. Despite all of this, I learnt some very important lessons as to what not to do in a situation like this. One thing it highlights though, is the fact that for all the carry on I’ve seen over the years from people who don’t understand risk management and incident management, the fact remains, being on the road with students is one of the highest risk factors possible. Driving to the conditions, avoiding peak periods of traffic and having a fatigue management policy and procedure in place is vital to reduce this transport risk that’s part of every trip away from school. Let’s put this back in context. We were going to a debating competition!!! Sounds very low risk and not even worth doing a risk assessment on, yet had the truck driver not reacted the way he did, our bus would have been cut in two and a few more sun-bleached crosses would have stood scattered at the side of the road, lovingly surrounded by flowers, tended only, in decreasing frequency, by the broken families who were never told what really happened that day.

0 Comments

Over the past three years, as I've worked on various outdoor ed programs, I’ve seen a pattern repeating itself over and over again. With a new group every few weeks, I've found the same kind of engrained beliefs the students have about themselves presenting again and again at the start of each program.

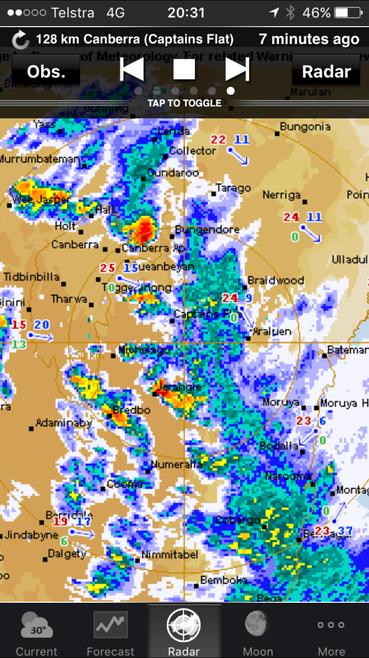

When the students arrive, I run a session on goal setting. In this, we outline why we set goals, how we go about achieving goals and why we should be setting goals outside our comfort zone! Despite this, it’s not until we actually get out into field and start doing some challenging activities that students get the opportunity to field-test their skill level and resilience. Often we’ll be running an activity where the students have little previous experience. As a result, they’re hesitant or even fearful of the activity. The feeling of pushing outside one’s comfort zone starts to solidify in the students’ minds. However, I've noticed an increasing number of students shy away from activities that involve any form or risk, or perceived risk of failure. Some of this feeling of fear is perhaps due to lack of experience. Other fears however, are often inherited from external sources such as parents and family who may have misguidedly told their children to always ‘Be Safe!’ ‘Don't take risks!’ and because their children are so perfect, they can't possibly fail… at anything! One of the problems this creates is an irrational fear of dangers that don't actually exist and the fear of failure to the point that it's better not to try, than to risk being seen as less than perfect. The number of ‘perfect’ children I now find who have such low self esteem and lack of self belief is astounding! When setting up activities we run, especially when we’re looking at abseiling, surfing, high ropes courses and even riding a bike, I say to the students beforehand, ‘Don’t always believe everything you think!’ I usually get blank stares, ‘What’s he talking about?’ I leave it at that! I don’t go into any other details before starting the activity. Whatever the activity may be, I make sure that it's designed to push the comfort zone and boundaries for each and every student. Because of their pre-existing self-beliefs and low-levels of resilience, more often than not the students will go into an activity thinking, ‘I can’t do it!’ It's really just their first line of defence to avoid their fear of failure. Whenever they tell me, ‘I can’t do it,’ I generally respond, ‘Why not?’ In return I usually get ‘Because…. Blah, blah, blah!’ By this time, I've tuned out as they’ll throw up every possible excuse to avoid trying. These excuses tend to come out in rapid-fire succession, just in case the first one doesn't sound believable enough, they've got the next one ready to go! What they're basically saying is, ‘What excuse can I make up to protect myself from possibly failing?’ and it's this fear of failure that's increasingly driving behaviours in students. However, unless there’s some pre-existing medical condition, or some real reason as to why they can’t participate, I ignore their complaints about not being able to do it and instead encourage them to give it a go! Whatever the activity, we’ll graduate it throughout the day to increase the level of challenge. For example, in mountain biking, we’d start with simple biking skills, how to set your seat height, how to pedal, how to change gears, how to brake, a very important aspect. We move on to how to go over an obstacle, how to go over an obstacle when moving at speed, how to go over multiple obstacles in succession and how to negotiate around berms, downhill at speed. The activity is therefore getting harder and harder, but it's graduating at a pace with which the students can manage. Suddenly, without realising it, the students are riding on relatively steep terrain covered with some serious obstacles. A couple of hours ago they were telling me, or more to the point, themselves, that they couldn't do it! With a ropes course, we start with low ropes, which are literally one step off the ground. They're simple stable challenges. However, after this, we ramp it up to a high ropes course where there's an increased perception of risk. We often have students who are afraid of heights and this is a great activity to seriously push them outside their comfort zone. It makes them feel fear, it allows them to confront their fears head on and I work closely with these students to pushing them through that fear and enable them to truly challenge themselves and their firmly held beliefs. Once you can get them to punch through those self doubts, then their attitudes change, their confidence growth with it. The same is true with surfing because a lot of students have never surfed before. Some are afraid of the water. Some are afraid of the surf. Some are afraid of getting eaten by sharks. The reality is though, you’re more likely to get killed by a vending machine falling on top of you than you are getting eaten by a shark. But people are still afraid. No matter what the activity, the biggest challenge for students always comes down to all of the irrational fears that run through their minds telling them they can't do it. However, once you get them involved and engaged in an activity, the fears disappear from their mind. They forget about all the excuses they made up as to why they couldn’t do something because their minds are now focused on the here and now and before they know it, they’re actually doing the thing they told you they couldn't. I love to see this when it happens and I use this to positively reinforce those affirmative risk-taking behaviours that the students have pushed themselves to do. In debriefing the activity, I revisit the issue of facing fears, happily saying to the student, ‘You’ve just achieved something that you told me you couldn’t do. Two hours ago you told me, “I can’t do it,” but what’s happened?’ I encourage all the students to respond individually. Invariably they’ll say, ‘I did it!’ And they’re really excited about it too. You can see it in their faces and in their smiles. They’re excited to have conquered their fear. They’re excited to have done something they’ve never done before. To conclude the debrief, I’ll do a summation then reinforce my original statement, ‘Don’t always believe everything you think.’ Suddenly, I see lights going on! Some students are having an aha moment! What I said at the start is now making sense. Whilst they mightn’t remember it at the start of the next challenging activity, I’ll remind them of it and consequently they start to further process how to better approach challenging situations. When students begin to realise their thoughts can shape so much of their lives in both positive and negative ways, this can become a powerful tool to help them master their approach to new challenges and experiences. Instead of telling themselves they can't do something, they've now got a power reference point of how and why they can do something they never thought they could. Using briefing and debriefing frameworks to provide relatable learning moments, is vital when working with teenagers who might not always feel comfortable nor confident in everything they’re doing, even if they pretend to be. Whilst life’s not all high ropes, mountain biking and shark dodging, when students can use these more challenging experiences and relate their success in these back to every day life, they start to become more resilient and realise they can push through other challenges they face. Relating outdoor activities back to a wider context in this way, can be extremely effective in helping teenagers to push themselves outside their comfort zones and grow. It helps them to adopt a better mind-set for the way they should approach the next activity, or the next family matter or the next big decision they need to make in their lives. Chances are if you do the same, it could help you to push through some of your own long-held fears and apprehensions. So remember, Don’t always believe everything you think! An operational management plan is essentially the standard operating procedures for your program. Now I hate the term SOP, because it always feels like it's a set of rules that's written down, which ultimately guarantees that nobody ever reads it. So what's the point? Like anything involving people, logistics and risk, it needs to be a living, breathing process that all staff are part of. It has to be clear in the minds of all staff what the process is to run a safe and effective program. With any experiential education, you need to have some very clear structures in place to both ensure the smooth operation of activities, as well as contingency plans if something goes wrong. Some organisations are obsessed with risk management plans and waivers, thinking this is all the planning they need. They've kept their lawyers happy and there's a document they can produce to prove they at least thought about something before leading the group into the valley of death. Well, there's quite a lot more to it than that and this is where many organisations go wrong. You’d think it goes without saying that you need a plan, an itinerary, a schedule, risk assessment, student medicals, permission notes, or at the very least a class roll! However, I’ve regularly seen the focus of planning to be on only one or two of these components, rather than properly addressing them all. You must address them all! There's no point in having an itinerary and risk assessment written and not having the logistics and staffing in place to execute your plans. You always need a functional end-to-end operational plan, that is flexible enough to handle multiple contingencies. Therefore, you need to plan for everything from the perfect operation to various “what ifs” for minor hurdles, emergencies and full crisis response. An effective response though has more to do with the staff’s mental state and ability to respond and adapt to a fluid situation, rather than a rigid written plan that's immediately forgotten when confronted with a complex crisis. I've seen this done very well, but also extraordinarily poorly, especially when people aren't operating programs all the time and they feel they need to make things up as they go. There's a huge difference between being adaptable and making stuff up on the run. So one massive hint here, Don't Make It Up As You Go! Have a well-structured, executable plan that everyone’s part of that can be quickly enacted if something goes wrong. What if the weather changes? What if an emergency happens? What if a crisis happens? Are you prepared to switch it up and respond quickly and effectively? I've seen some great written risk assessments where I have mused, ‘wow they've thought of everything!’ but then looking further on, no contingency plans nor any real idea as to how to manage an emergency or crisis. It's Never Nice Getting Hit By This Emergency Services I've seen and worked on programs (thankfully not run them) where the organisation had a ‘nothing will ever go wrong’ approach. This is where everything is done on razor thin staffing, based upon the idea that everything will go exactly to plan and I mean exactly to plan! The danger of this, is firstly, it's idiotic in the extreme. When you're dealing with groups of students and staff in different locations and involving vehicles and equipment, something could eventually go wrong. If you have no flexibility and adaptability factored in, then you're asking for a lawsuit and in fact, you deserve the horrendous experience of being dragged through the courts for your stupidity. I never felt safe, nor comfortable on this program. Thankfully, when I brought it to the attention of the organisation and they couldn't see the problem with it, I left and found another place to work that did.

This ‘razor thin’ notion, usually done to ‘save money,’ that works off the basis that everything will go exactly to plan, just increases the pressure, stress and fatigue on staff, which adds to the inevitability of something going wrong. Philip of Macedon (Alexander The Great’s father) put it very nicely. ‘No plan survives contact with the enemy.’ So with that in mind, here's an outline of how I develop an operational management plan:

If you plan around these 10 steps, then you're well on the way to having a safe, enjoyable and rewarding experience for everyone involved. Managing medical concerns at school and on excursions is one of my biggest worries as a teacher! Anaphylaxis is at the top of that list, since a reaction can be almost instant from the allergen and has a cascading effect. This means the longer you leave it, the more difficult it is to recover. However, despite this serious concern, it just means effective strategies need to be in place to ensure preventative measures are the number 1 priority.

In outdoor education, we usually run our programs a considerable distance from emergency medical care. As a result, this adds an additional layer of risk to any trip away. However, rather than worry about this and feel as though it’s too risky to take kids away, my focus has always been on effective preparation and management. This ensures that the chances for an anaphylactic reaction becomes so low, it’s not an issue. If a student’s medical profile is flagged with an anaphylactic allergy, I’ll phone home and talk to mum and dad. What I need to know when I call is what are the specific triggers? Can they have foods which might contain traces of the allergen? When was the last reaction and what happened? Even though this information might be in the medicals, I prefer the first hand information from parents, so I can effectively brief my staff. I also want to know how well their son or daughter manages their allergy. Are they aware of what can happen? Are they aware of what foods they can and can’t have? This information is vital in helping provide teachers with the best management strategies in the field. As an example, on one program, I had 247 students out in the field for a week long camp. 11 of the students had allergies which could result in an anaphylactic reaction. Based upon the information from the parents, and the fact some activities were hours away from emergency care, I carefully placed students with the highest needs in the closest proximity to emergency healthcare facilities. In one of the extreme cases, given the number of allergens that the student was affected by, I asked his mum to provide and pack the week’s food in an esky for her son and I provided a clean stove which was specifically for his personal use. At the end of the day, it about clear channels of communication between parents, teachers and the child. Even though all staff are trained in first aid and anaphylaxis treatment, effective preparation and prevention is far more important. For every activity we do, we go armed with a list of dietary requirements and only shop according to each individual excursion. We don’t plan meals months in advance to save time. It’s about providing the best meal options for each individual group. This way, we’re prepared and able to ensure we provide a safe environment for every child and a wonderful memorable experience away from school. Food on camps is tricky, but not in the sense that it's hard to do well, there's just so many considerations when you're catering for a diverse school group. Added to this, you often don't know the kids very well. Before camp we do a lot of work preparing for any group and no two camps are the same. To begin with, we look at medical risks and dietary needs. What concerns are there? Do we have kids with allergies? Will some additives make them sick? Will bread and milk cause them to be ill? Can they eat meat? Is it the right sort of meat? Are there any other foods are of concern?

Having catered for so many groups on camps and residential programs, one of the key concerns was that everything has to be ‘normalised.’ Even though I might’ve been catering and cooking for a number of different dietary needs, because they’re kids, I never want anything to stand out or be remarkably different. The last thing I want to hear is a whiney toned, “Why do they get that?!” So if I was cooking burritos for example (which kids love), I'd cook a variation of the burrito for everyone to enjoy. Some have mince, some have chicken, some have tofu, some have beans. Some have tortillas, some have gluten free tortillas, some prefer just to have it on the plate! Regardless of the mix of ingredients and the time that goes into this, the most important thing from my point of view is every student’s well-being and part of that is making sure they don’t feel ‘different’ a meal times. I’ve been to far to many venues that provide vastly different meals for the kids, making them feel left out and even isolated due to their dietary needs. I won’t have any of that on the camps I run and it’s not unreasonable to expect the same! To be honest, I love buying different foods when I go shopping. I think of all the cool combinations I can do for pizzas, curries and salads just to name a few! Whatever the menu is, I just love wandering around and searching for the best combo to make sure my one meal, can be eaten by all! This does take time, but once you’ve got an idea of a meal plan, each time you have a student with special dietary needs, it’s now only a matter of checking the plan and grabbing the right ingredient! On a visit to the US I took some time out to go skiing in Park City. It's a fantastic resort and an awesome historic township. It now even has an Australian run café, which meant I could have a decent coffee (all the important things being from Australia). I’d prepared myself to go a month without decent coffee, reliant on bitter or burnt espressos as a backup plan. I was however, pleasantly surprised to find myself standing in front of a recognisable Australian business and safely drinking a good cup of coffee.

Despite this extremely important tangent, what follows has nothing to do with coffee. It was early in the morning on a crisp crystal clear day over on the Canyons side of the resort. I was skiing past the ski school when a sign caught my attention, “Please, No Parents In The Learning Area!” I laughed, as I knew exactly why there was a need for something like this the moment I saw it. Whilst it's very important for parents to be involved in their child’s education, there's a right way to go about it and a wrong way to go about it. More often than not, parents, generally through a lack of understanding go about things the wrong way and many of them constantly insert themselves into situations where they should just stand back and allow others to teach. From what I’ve seen over my years of involvement with education, Helicopter & Tiger parents, need to relax, find themselves a hobby that doesn’t involve them living vicariously through their children. Whilst the underlying belief these parents have is that they’re ‘helping’ and making sure they get the ‘best’ for the child, the reality is that they’re doing more harm than good and wasting their own life and opportunities at the same time. It’s probably easier to remove the salt from the ocean than it is to remove the helicopter from the parent, but seriously, they need to back off and let their kids breathe and experience a few things in life for themselves. This doesn’t mean that everything should be done at arms’ length, but I can understand the need for the sign as over-involvement of parents can be just as bad, or even worse than under-parenting. I realise it is a challenging balance, but if you look at it from a work point of view, how would everyone feel if someone went from department to department telling everyone how their job should be done. From marketing, to finance and the janitorial services how would everyone feel if your clients hung around giving instructions on how their work should be done? It wouldn’t be long before security was called and the person was ejected from the building. I would have thought the whole point of taking your kids to ski school is so that you could ski somewhere awesome yourself. Hanging around offering suggestions or taking photos would be the last thing on my mind. I would have ditched the kids and headed up the closest double black only lift. Ski school and school in general is a great sort of child minding service, which hopefully employs talented instructors and teachers who will be able to care for your children and teach them something far more effectively than you can. This, of course, eventually pays off later on, as you’ll be able to ski with your kids, until they get way better than you and then leave you for dead, suggesting perhaps you should go and have some lessons. However, from this the most important thing is that sometimes parents need to be able to step away from a situation and allow their children to be taught by others. If they’re not prepared to do that, then why not teach them everything they need to know themselves? This would seem to be preferable for many parents, until they realise the reality of how much time, energy, experience and effort goes into teaching others. At some point, parents must let go and if they haven’t by high-school years, then the damage they’re going to do over the proceeding years is significant. Again this doesn’t mean parents should have no involvement, but appropriate experiences should be looked for where that increasing independence can be gained. Some effective programs I’ve worked on have been medium and long-stay residential programs, in which there was little choice for those helicopter parents but to stay away. If medium and long stay programs aren’t an option for your school, then perhaps erecting a barrier near the entrance is the next best option. At the end of the day, it will enable students to have a far better educational experience than the endless hovering could ever provide. For me, as I said, I’d just leave them at the ski school and allow them to try new things, slip, fall and get back up again all by themselves. It’s the learning through these experiences that make the best skiers and the snowboarders, not the manic parenting and suggestions from the side. Perhaps, as in Park City, a giant sign is just what’s needed for all of our programs to remind parents of the fact that it’s time to let go a bit and let their kids do something a bit ‘risky’ for themselves. Nobody really likes taking kids into hospital. Most of the time it ends up being the teacher who’s got time off, or the last person out of the room! Let’s be honest it’s a crap job that nobody wants. Firstly you have to take at least two kids with you, so you’ve got one injured and one bored. Secondly the wait… there’s no such thing as a fast track in emergency unless you’re not breathing although arguably by this point you're probably beyond the services available in the emergency ward. Thirdly have you ever been able to get a decent coffee in a hospital? The trip to hospital all starts when an injury is more serious than your staff can manage. I've had all sorts of visits with students, from fractures, to cuts, to unknown issues each visit if often a unique experience... My longest wait was 8 hours and this gave me the opportunity to talk about all sorts of things with the student. It's amazing what you find out about life the universe and just about everything when chatting! However, my weirdest experience was when I took one of the kids in with multiple cuts after he took a dive in a bed of oysters. I won't go into the gory details, but he was a mess to say the least. We sat and waited for some time after seeing the triage nurse, who rifled through the stack of papers which were suppose to be a medical 'summary'. When the nurse finally brought us in to the examination room, she took one look at him and proceeded to fill a tub with warm water and a dash of disinfectant. She then said to me 'here you go, take this into the waiting room and clean him up'. I looked at her for a moment wondering if she was serious... Yes she was! I looked back at her and said 'can I at least have a pair of gloves'. She half indignantly grabbed me a pair of glove and off we went. I sat there apologising profusely to the couple sitting next to us as I cleaned out the painfully deep wounds and collected a pile of tiny oyster shells as I did. I've heard of cut backs but seriously do I get a discount on my Medicare levy for do it yourself work in hospital? Anyway, we were there about another hour and a half and the boy ended up with stitches in his hand and bandages everywhere. To be honest I still try and avoid the hospital trip (mainly because of the bad coffee), but at the end of the day when you're responsible for the kids welfare and safety, prompt action and quick decision making to get them to hospital can mean the difference between an injury becoming an extremely bad injury. So really it's always better to err on the side of caution and take them in to be sure, rather than risk it just to avoid a long wait. At the end of the day, you can always get a coffee on the way home!

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|

Copyright Xcursion Pty Ltd 2015-2023

RSS Feed

RSS Feed