|

The debrief is one of the most powerful teaching and learning tools you can use. However, it's either not used at all after a learning experience, or done poorly when the guide isn't sure what their objective is. For people who aren't familiar with the concept of the debrief, it's a post activity discussion that's designed to reflect on how everyone found the activity, how they might have been challenged by it and what they learnt from the experience. The aim is for everyone to be able to take a moment and self-reflect.

Once we can self-reflect, we can learn how to approach different situations in a more proactive manner and become far better equipped when faced with life's challenges. The first step of the debrief process is to make the debrief setting comfortable and confidential. Often participants are confronted with a weakness or a failure in an activity. It's not all going to be capable people saying how well they did and how amazing they are and if this is the way your debriefs go, you're either working with infallible people or you're not asking the right questions. It should be made clear that anything said within the debrief remains within the confines of the debrief. That way, there's the potential for an increased openness of the participants to share and potentially be vulnerable in the process. Next remove those who want to disrupt. This has rarely been an issue, but if it is, then you're better off without everyone. Some people will say the ones you remove are the most in need of debriefing skills. Maybe they are, but in my experience, they're usually the ones who have no idea and will just go through life disrupting everyone and everything they touch. I'm not here to suggest ways to save every single student. I am here to help those who are wanting to help themselves and who want to learn and grow from their experiences. Now for the biggest challenge: ask the right questions! This is a difficult one, as every activity and every group is different. However, as an experiential educator getting a feel for the dynamics of the group and how they've coped or not coped with the activity, can help shape your thinking. If everyone found the activity easy, I'm not going to go in with a question about facing challenges. Conversely, if the activity was really hard, I'm not going to shy away from the fact people were pushed. So what do you want to achieve with a question? Again this is critical, if you've got nothing in mind and you just need to do a debrief because you were told you had to, there's not going to be much reflection happening here. The activity, the question and the goal must therefore all be linked together. A fairly simple example of this is on one canoe trip, we were smashed with rain, like a massive amount of rain that was relentless. The conditions were not dangerous, just uncomfortable. The decision about to what to do was placed with the group. They wanted to leave the shelter we had under a rocky outcrop and continue. So we did! We pressed on for another hour to reach camp, then everyone had to work as a team to get tents setup and a fire going as quickly as possible. That evening around the fire, we talked about decision making and team work. Not everyone wanted to go on. Some were happy with the shelter, but the students made the decision and we supported it. When we posed the question about the decision making process, the students who made the decision in the end had felt nervous about it, because they didn't know if it were the right decision. This led into a more detailed group discussion on decision making. What's right? What's wrong? Why do we second guess ourselves? How should our decisions be guided? This discussion exposed some interesting group dynamics and it also showed how some were prepared to make decisions and take responsibility for the consequences. As one of them said, “Sure we got wet, but we made it to canoe safely and we’re not still stuck there under the rock.” Everyone was exhausted that night and we could have just gone to bed. If we had, the group would never have had the opportunity to reflect on the day and the way in which they made some very mature and proactive decisions that resulted in the best outcome possible for the group. Debriefs are a powerful learning tool and it's so important to both understand them and put them into practice for all your activities. The debrief shifts a ‘fun time’ doing an activity into a real learning experience, that provides huge educational value. The more you do this with your students, the more they will learn and grow as individuals.

0 Comments

A lot of people think more is better. The more information you have, the more documentation you have. The more plans you have, all make life so much easier, better and safer.

However, the reality is quite different. Ironically, the more information someone has, the harder it is to make an informed decision. I’ve seen risk management documents which run to 70 pages in length, which nobody is going to read for one, but also, even if you did read it all, there’s way too much information contained within those 70 pages for anyone to make a logical and informed decision. More is most definitely not better. As humans, our brains can only take in so much info and analyse it before it gets overwhelmed. Too many possibilities become too hard to rationalise and think about logically and the more information and possibilities, the harder it is to respond and make any sort of informed decision. This is why we see people in high stress situations make very poor decisions, which result in bad outcomes. It’s not the lack of information at hand. It’s too much. Instead of having reams of paperwork, which is supposedly there to help people run programs safely, you’re far better off to only look at key points of data to help you make a far more informed decision than the alternative. Whilst this may seem counter-intuitive, the fact is that we’re not good at decision making as the stress level increases and the amount of information to analyse increases. We become myopic and our field of vision and understanding narrows. That’s why, sadly, so many coronial inquests on the surface seem so simple and straight forward. Why wasn’t this simple decision made at this point in time to prevent the fatality from happening? Chances are that there was too much information at hand. We therefore need to simplify what we’re doing and how we’re doing it to improve our decision-making abilities. Nobody is going to read or even be able to use huge documents. They’re only really useful to lawyers post incident to spend more time than is reasonable for them to photocopy and read through so they can bill clients for it. Whilst that’s wonderfully profitable for lawyers, it’s actually not much help to you in the field. How do you filter out the noise and get to the key information you need? That’s challenging, because each activity is situational. However, if you focus on your key risks and supervision responsibilities, then you’re well on the way to making good decisions. What’s the weather like? What’s the group dynamics like? What are the key activity risks? This is a great start. Also delegating responsibilities and positive team communications and dynamics, is a great way to reduce the burden of decision making on any one person to enable fast and effective reviews and analysis of the information at hand. You often come across people who carry risk management documents on them as their way of effective risk management or responding if something doesn’t go to plan. However, this is problematic in that the time it takes to find something within that document that may be useful in a critical incident, is just time wasted in actually dealing with the issue at hand. Whilst this doesn’t mean that this preparation is time wasted on developing good risk management systems, processes and documenting this, it does mean that you need competent people on the frontline running programs who can make informed decisions based on a reasonably small set of data. This takes training and practice, but if you realise that to begin with, the more information at hand, the more difficult it is to make informed decisions, then you’re well on the way to being able to more effectively handle stressful situations and incidents and come out of them with a positive outcome having managed and mitigated the situation at hand. Therefore, don’t let yourself go down with myopic tunnel vision. Work out what’s important and filter out all the noise. Run some training scenarios and make sure you’re ready for whatever comes your way. Welcome to the Xcursion Risk Tips. These tips are designed to save you time, money, reduce risk, and improve safety for all of your programs. Today, we're going to look at students cooking. Phew, yes you probably just reel back from some certain experience that you've had out on a program where our kids cooked you something. Now, I've had both ends of this spectrum. Some kids well, you really wouldn't trust what they cook or what they put in that meal. However, other kids can cook so well. It is great to see them get involved and actually cook something.

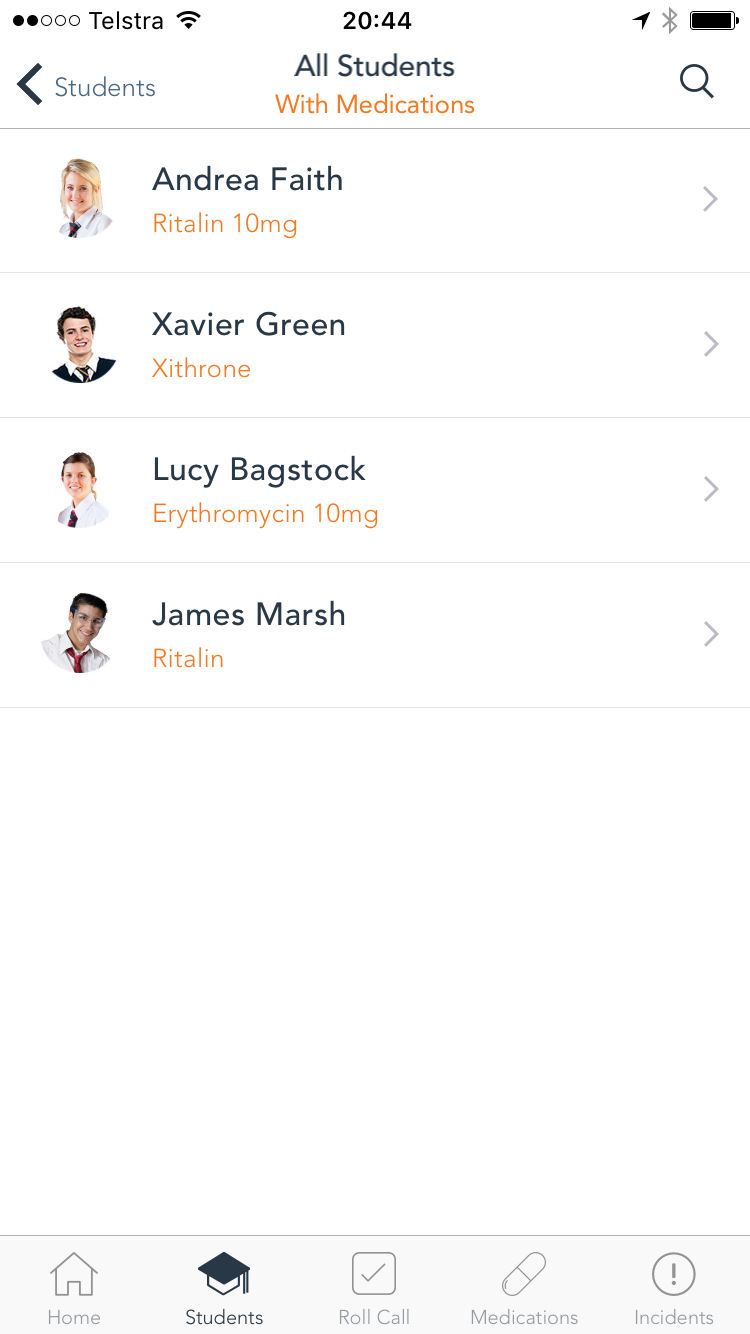

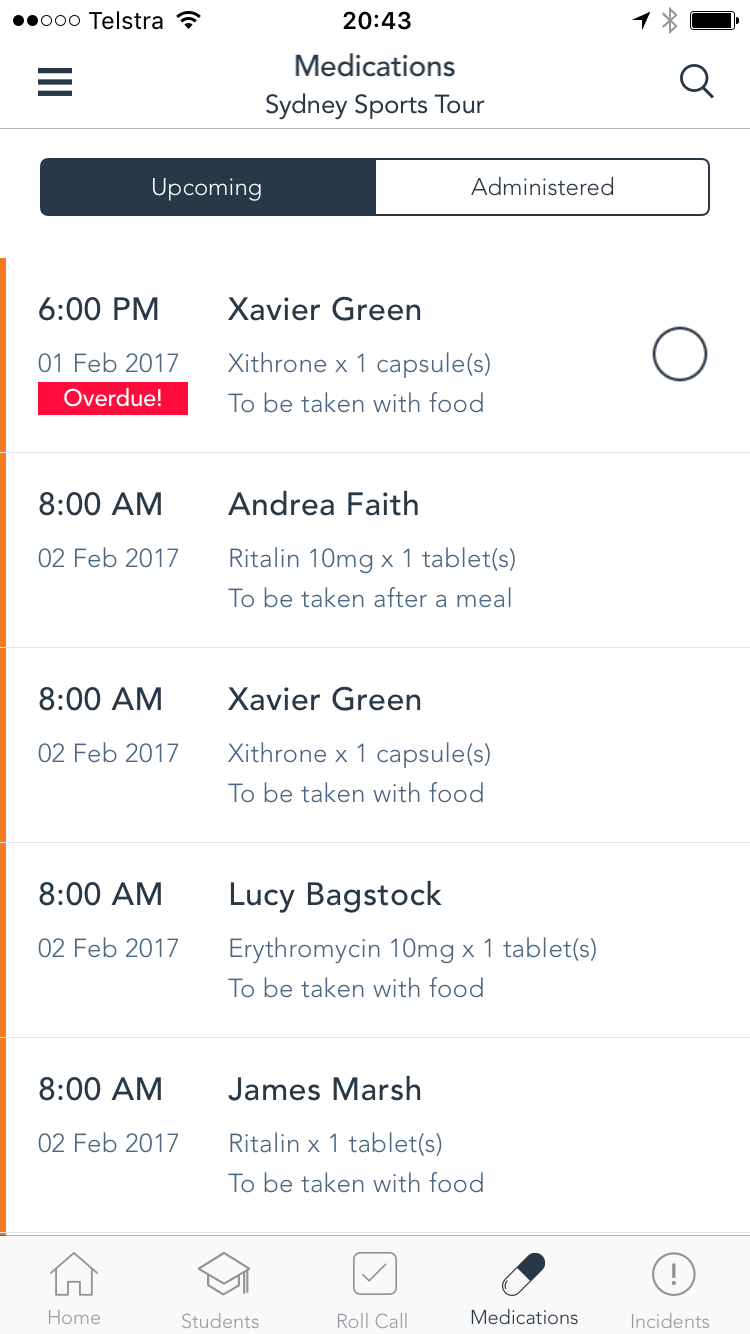

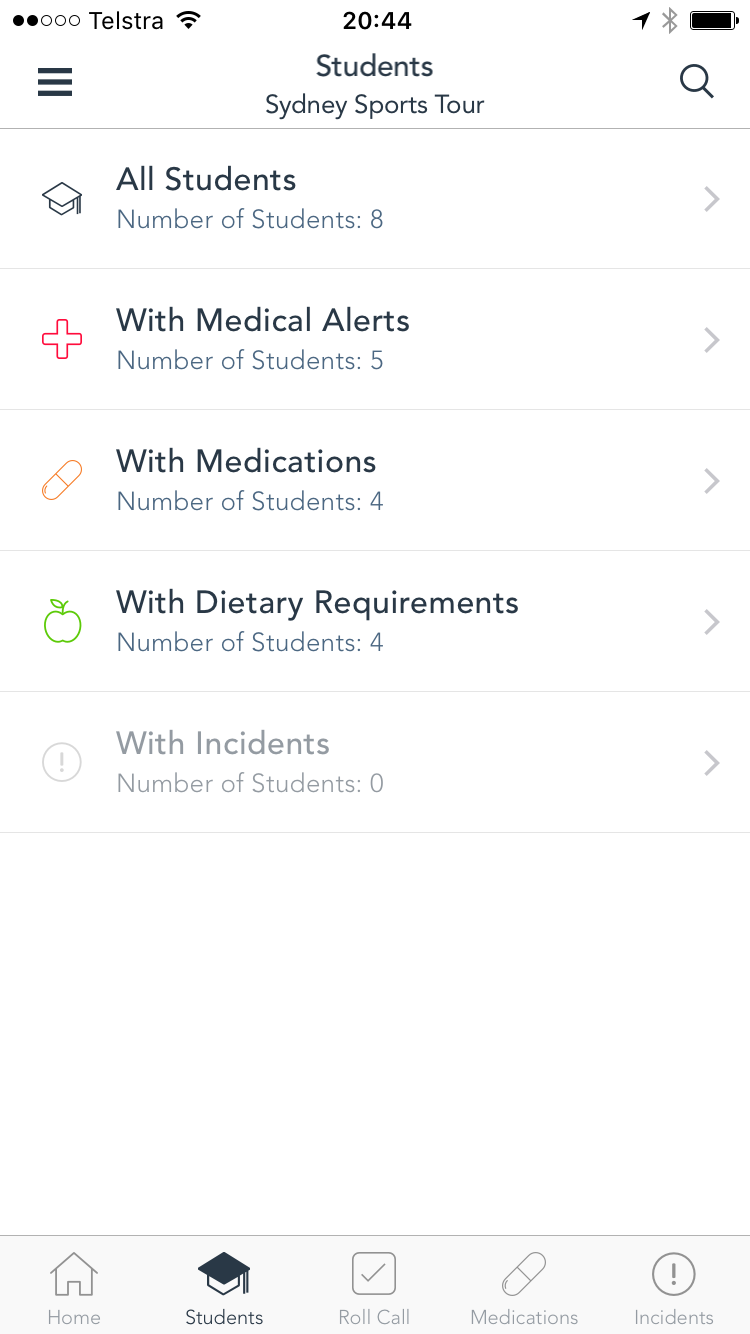

I've come across schools and I've come across teachers who are really hesitant to allow kids to cook. But seriously, at what point do you let go and enable kids to take ownership and take responsibility and do something they really want to try? This is something that not a lot of kids get to do at home. So the opportunity to cook whilst on camp is really important and they love to try and impress you with their meals. There are a couple of risks involved in this and a couple of hazards. The two main ones that we want to look at are knives and fires. Firstly, it's the preparation of the meal. It's cutting up everything on the cutting boards and making sure that they don't cut the veggies and themselves with the blunt knives. Now more often than not, you're going to find blunt knives on camps because you can't trust anybody with a sharp knife. Unfortunately, with a blunt knife, they're more risk of causing injuries, than sharp knives. Because the pressure that's applied to a blunt knife is far greater than the pressure you need to apply with a sharp knife. So at least have your knives slightly sharpened so that they're not totally blunt and can cause really really bad injuries. One student I had on one of my programs, he managed to stab himself in the webbing of his hand with a knife. How we managed to do that? I don't know. But he was cutting up the vegetables and just came up to me and said, "Oh Sir, Sir I've cut myself." I was like, "How, how did you do that?" I mean, it was an impressive cut and we managed to apply pressure and patch it up ok. But I was astounded. But basically what he had done was he had pushed so much pressure on the knife, flicked it off the vegetable and skew it himself in the hand. Now that's one part of it. You really do need to monitor and supervise effectively when the kids are cutting things up. Once they're all cut up, the next thing is the fire. Or most likely you're going to get something a Trangia. Now a Trangia for those who don't know, is this little stove and it's got an alcohol burner in the middle, and you pop it in and put your pot on and away it goes. Many schools I've worked at, many programs I've seen to begin with, didn't actually contain these fires or didn't monitor this effectively. This is the next really critical hazard that you need to manage effectively for when students are cooking. So what you want to do is set up what we call it a Trangia circle. Now a Trangia circle can be done just with a small bit of rope and you put a big circle right around and the pots go in there, nobody or nothing else goes in there and your fuels go well away from where you are. So with that in mind that you have your contained cooking circle, and you only limit the number of kids near the cooking circle. You don't need three kids cooking in one pot. You need one student cooking in one pot. So, limit the numbers around the cooking circle and actively monitor this. Don't cook your own dinner at this point in time. One great solution is get one of the kids to cook. This has worked many many times that I've often had a lot of student meals because they've offered to cook for me. At this point in time, you don't want to be cooking because you need to be supervising what's going on and monitoring that fire circle and monitoring the way in which it's being conducted. This is critically important to reduce the risk of burns and scalds, which are some of the highest numbers of injuries that you get when you have kids cooking on programs. So you monitor that. They cook you dinner and you get to stand around drinking a cup of coffee whilst you watch them cook your dinner. What's not to like about that? One of the problems I've seen is when staff are cooking their own dinners is that they don't have that level of supervision. They become too focused on their own meal and at the end of the day, you're the leader, you're looking after these kids, you can eat later. So, use that opportunity to try some kids cooking and that the reaction that you get when they cook something for you and you are able to share a meal with them is really good and it's all part of that bonding experience. It's all part of that journey of a camp. That way you can develop rapport with your kids in such a unique setting. So two main risks for cooking with kids, it's not the taste, it's not the flavor, it's not what they cook although sometimes they can burn things and it's horrible, but we won't go there. But the two main hazards are cutting with knives, prepping meals, and also the cooking circle or the Trangia circle. If you can effectively supervise these two, then you've seriously reduced the risk of something going wrong on your program, and the kids are learning from this experience by cooking meals for themselves. At Xcursion, we are often asked questions about data security and sovereignty. Not the most exciting question, but an important one all the same. With student medical records, security is a must. However, what do most schools currently do? They tend to either use paper printouts, which are really hard to track and I’ve seen folders of these go missing a number of times. No security, no track, no idea where that highly confidential information ended up. Others use email and things such as dropbox or google drive to share medical information for camps. Whilst this is a slight step up from leaving a folder around, it is in fact still not a suitable way of data management. Once you share something on google drive or dropbox, there’s every chance that the information on that drive isn’t located in your country of origin, which is important when it comes to student medical records, which in most counties need to be stored only in that country of origin. You then still have the same problem once you’re heading out for school sport, school excursions or activities. How are you going to safely carry and use the information you need? Most of the time we’re back to using print outs, which can contain students home addresses, medical issues and a range of other private healthcare and personal information which needs to be protected. This was a problem we faced years ago before we developed the Xcursion mobile app. Data security was literally non-existent for our school programs and we needed a way to easily, securely and effectively access that information and use it when it’s needed. The rest of the time, we wanted it locked away and secure from transfer or loss. Therefore, we encrypted our entire Xcursion mobile app platform and databases to ensure that all of our client data was secure and hosted in their country of origin. This way we were able to provide much better data security than before and ensure the most important information was both secure and accessible anytime a teacher needed it for any sort of medication administration, incident report or just a quick call to parents to let them know everything was ok.

How are you securing your information? As experienced teachers, we know how hard it is to keep up with so many responsibilities in and out of school, so if you’d like us to help you make medical information more secure and easier to manage for all your school excursions, school sports and activities, then get in touch today. Recently, I was reading a fascinating book about airplane crashes and how poor decision making ultimately led to disaster and the huge loss of life. What was striking about this was the similarity to so many coronial inquests for outdoor education incidents.

Much like many fatalities on outdoor expeditions, each of the airplane disasters could have been avoided. However, fatigue and poor decision making ultimately led to disaster. So why are we so impaired by fatigue and why do some organisations still not see this as a major problem? One school, which shall remain unnamed, for which I worked a number of years ago, were vehemently opposed to any discussion around fatigue, despite numerous concerns being raised by staff around the impact it was having on the welfare and well-being of the staff. The implication was that we were just being lazy and trying to get out of work. I would suggest 80+ hour weeks backed up by driving vehicles full of students was a bit over the top. However, I’m not going to dwell on the rest of that experience, other than to say it was a pre-loaded disaster waiting to happen. When we’re fatigued, a number of things happen which reduce our ability to make clear, informed and reasonable decisions. The harder we try, the less effective this becomes. Our focus narrows further and further into a tunnel vision that cripples our ability to make sound, reasoned judgment. This was evident in the cockpit recordings of each of the plane crashes outlined in the book. Instead of clear, thoughtful and decisive action, mistake, after mistake, after mistake was made, culminating in the inevitable plane crash. Experienced pilots forgot their training. Simple corrective actions weren’t taken. The same is true of fatalities in outdoor education in which fatigue adversely impacts on the ability of an instructor to make reasonable, informed decisions. Research has shown that multiple shifts of work and not sleeping for 24 hours (which counts poor/broken sleep within the mix), has the same effect on decision making that being drunk has. Do we ever allow teachers and instructors to be drunk at work? No! So why do we allow fatigue to be overlooked? If you examine the black box flight recordings of the conversations inside the cockpit, it becomes abundantly clear that for example, despite evidence to suggest that all the pilots needed to do to save the plane and those they were responsible for was to push down on the controls to increase speed and prevent a stall, they kept pulling back on the stick, consequently condemning the plane and all onboard. However, before we call them stupid, which is the temptation of a back-seat pilot with no airtime, let’s look at the effects which fatigue has on people and why it’s not surprising that such poor decisions were made in the air and also in the field, for so many expeditions which have gone disastrously wrong. When people are fatigued and/or drunk, their reaction time slows, their ability to solve complex problems is significantly inhibited and their ability to perform even the most regular and simple tasks becomes compromised. The only solution for fatigue, is sleep, not push through it as a former boss of mine would always profess was the way he always did it and we should do the same! That, in my opinion, is idiotic in the extreme and will eventually result in someone getting killed. However, you can always learn a lot from idiots as they demonstrate the dangers of what not to do. Often this can be even more beneficial than someone telling you what you should do. Good decision making is one of the best risk management strategies you can have. You see something that hasn’t gone to plan, doesn’t fit or doesn’t feel right. You assess the problem, adapt and respond accordingly. Good outdoor leaders will continually do this throughout any program. Most of the time, what they do isn’t even noticeable. Other times, it’s clear that there’s a problem and there’s a shift in plans to address it. The same is true with airlines. Most of the time you have no idea that corrective action was taken, which is the way it should be. Unfortunately, when we’re fatigued, that vitally important, broad problem-solving skill set stops working. We can only focus on single tasks and, even then, we might only be able to focus on a single part of a single task, which is even worse. Often fatigued individuals will also focus on something that is completely irrelevant to the problem at hand. Instead, they become entrenched in a minor detail and they can obsess over it, as it’s the key to solving their current problem. However, their tired-self can’t even rationalise the fact that they’re grabbing onto something which is completely pointless, again due to their diminished capacity to make rational decisions. Unfortunately, in outdoor ed incidents, we generally don’t have first hand recordings of the events as they transpire, which we do have for the airline industry. Listening to these recordings, it becomes clear that minor and irrelevant concerns become the sole focus of someone who is fatigued. The death spiral starts and there’s no way out. If you compare this with coronial inquests into outdoor education fatalities, on many occasions, you can see how fatigue might have impaired judgment and might have contributed to triggering the repeatedly poor decisions and the downward spiral which ultimately resulted in the fatality. Now not all outdoor ed fatalities have fatigue as a contributing factor, but if we’re aware of the fact that it’s one of the most dangerous problems we can face even as experienced instructors, then we can put systems in place to manage and avoid fatigue and it’s related hazards. If we don’t want staff to be working ‘drunk’ from fatigue, then we must have good systems in place for managing this. How long is an acceptable shift? What are the tasks that each staff member is doing during this time? What driving is involved? Can the load be shared? What if someone feels fatigued? What backup plans do you have in place? The outcome of each of the airplane crashes was that systems to monitor and address fatigue were introduced, the result being, safer air travel. For outdoor education, this is something that must be addressed. It can’t be pushed through. It can’t be ignored. It can’t be put off for a discussion later in time. The end results, like the fatal vehicle accident in New Zealand where the teacher fell asleep at the wheel, are self-evident that fatigue and good decision making don’t go hand in hand. Do you have a fatigue management system in place? If not, make it your number 1 priority today as it’s vital that we and our industry ensure we keep safe those for whom we’re responsible. It’s essential to have instructors with clear heads and great decision-making skills, so that every outdoor experience is a wonderful and rewarding one for everyone. Risk management in schools is an interesting and concerning problem. There’s nothing in teachers’ training which helps them to understand the role and responsibilities of running activities outside the school grounds. In years gone by, this wasn’t too much of a worry as most teachers weren’t involved with the sheer volume of additional programs, excursions, activities and overseas trips which now form part of a normal year at school.

The only education that teachers seem to have in this is that at some point, they’re involved in a trip somewhere doing something and rather than having any actual training to be able to manage and help run whatever it is in which they’ve now found themselves involved, they’re entirely reliant on learning something about what they should be doing through osmosis. The expectation that they absorb something at some point in time which then magically enables them to manage risk in a well planned and professional way is ridiculous in the extreme, yet that’s basically the industry standard. Sadly, osmosis is a rather unreliable means through which people gain even a decent baseline level of any sort of skill, let alone risk management. It’s like letting your English teachers learn about a text for the first time as they read it with (or slightly behind) the class, or your maths teacher, teach themselves by reading a chapter ahead and asking the other teachers a few questions about ‘this whole algebra thing.’ Parents would be horrified and continually write angry emails to the school if they knew their children were being taught by teachers who literally knew nothing about their subject areas. Why is nobody upset when that same lack of skill and understanding is being applied to situations which place students at real risk or harm? Why is risk management training such an afterthought? Why do schools rely on osmosis for one of the most critical things required to keep their students safe? Is it because they don’t care? Most likely not. Is it because it’s too expensive? Hardly, as most training days are less than $500 a day and the cost to investigate even a minor issue is viciously expensive and can easily run into the thousands of dollars. Could it be something that they think they can contract out and not worry about because it’s now someone else’s problem. Perhaps they think they can do this, yet ultimately, they simply can’t contract this out and absolve themselves of any responsibility. If only there were an easy answer to this. There is some level of naivety in all of this and what’s commonly known as unconscious incompetence. You don’t know what you don’t know. So if you don’t know it, then how can you be expected to do something about it? Unfortunately, this is not considered a reasonable or acceptable defence when something goes wrong. It just makes you look more idiotic than before and even a mediocre barrister will maul the hell out of a teacher who tries to use this. The ‘I didn’t know’ defence has sadly been used in coronial inquests and no amount of ignorance has ever brought a deceased child back nor mended any shattered lives. So if training isn’t too expensive and it’s not too hard to do, why is it overlooked? I’ve often had the reply from teachers ‘I’m just a classroom teacher, so I don’t need to do anything like that.’ Yet these same classroom teachers are taking students down town, interstate and overseas on study tours, sports trips and cultural immersion programs. Just because you’re not going white water canoeing in South America, doesn’t mean you, your students and the school are not exposed to a huge range of potential risks from cultural misunderstandings, to political and social risks and poor student behaviour, just to name a few. Every time teachers leave the school gates with a group, they’re responsible for the safety and well-being of that group and like the English teacher reading the text as they go, teachers regardless of subject expertise, should not be out on a trip, anywhere, doing anything and making it up as they go. In my twenty odd years in education (some more odd than others), the overwhelming trend has however been to allow totally inexperienced and untrained teachers to take groups out and make stuff up as they go. This is wrong and at the end of the day, luck always runs out and situations like this will always end badly. Rather than rely on the magical fairy tale land of risk management through osmosis and relying on making stuff to as you go, it’s time to up the ante on teacher training and enable those keen and enthusiastic teachers who want to improve student learning through amazing real world experiences, to undertake some real risk management training and properly build their skill-set around good risk management practices so that every trip on which they go, is a memorable one for their students for all the right reasons. When we don’t know what we’re doing and we’re expected to have answers or manage risk, this is a massive problem. How can we be expected to put systems in place and plan for contingencies if we don’t understand the situation or context of what we’re expected to be doing.

Many teachers find themselves in this exact situation and are expected to plan for something about which they know nothing. At this point, the major activity and operational risk comes from the person not knowing what they’re doing, rather than the potential inherent risks of the activity itself. Do we let inexperienced drivers get behind the wheel without any training or supervision? Thankfully not. Yet why are so many teachers allowed to run sports, excursions and activities with no idea, training nor experience in what they’re doing? It literally makes no sense at all to allow someone to take on a role which requires them to plan for and mitigate risks, if they have no idea themselves. The increased risk here comes from the person not knowing what they’re doing at all and they’re simply making things up as they go, which is never good in terms of risk management. A number of years ago we came across one such group on an expedition. We were in Kangaroo Valley and just starting out on an expedition when we came across a group just finishing an expedition. In talking with them, we quickly realised they had absolutely no idea what they were doing. Their whole risk management plan was apparently based upon the fact that one of the teachers went for a walk and saw a snake, therefore they went canoeing instead because the risk of the snake was too great. I really want to laugh at this point as on that exact same river, I saw a 3 metre Eastern Brown Snake in the water and then it slithered up onto the place we had just had lunch, so seeing a snake in the wild and basing your decision on risk management around a single sighting of a snake seems quite idiotic to be perfectly honest. Essentially these guys had been out on a multi day canoe expedition with no canoe instructors, no maps, no communications devices and no backup plans. Everything has to run perfectly for them to be ok, which relying on luck for your management of risk, is never a good thing. One wonders how this group was even allowed to go out on this trip with such a poor basis for the management of the inherent risks, let alone the operational risks which were so obvious to this trip. Unfortunately, trips like this go out every day with no idea what their real risks are and the consequences of this can be horrendous if something goes wrong. The only way that this sort of situation can be avoided is through training and experience. If any organisation is sending staff out untrained and unprepared in terms of risk management, then they deserve everything they get if something goes wrong. Schools don’t allow untrained teachers in the classroom, so why do they allow untrained teachers in the field. Whether the teacher is running the trip or not, they need to understand what they’re doing to ensure they’re capable and effective in managing the risks involved outside of the classroom. Therefore, they need to be trained and experienced in general risk management, as well as activity or program specific risk management, so they can minimise the risks involved. The risk of not knowing what you’re doing is far too great and negligent when there’s so many opportunities to get trained and get up to speed with factors of which you should be aware and doing the right things to ensure you’re running awesome, experiential educational programs. If you feel like you don’t know what you’re doing and don’t understand the risks involved or just need a refresher, then get some training today so that you can confidently manage risk no matter what the situation or context. Thus, always run awesome, educational programs for all your students. For the adventurous rock climber, Mount Arapiles in Tooan State Park Victoria is an absolute must! This is a world class climbing spot and regarded as the best in Australia, attracting locals and international climbers alike. Four hours North West of Melbourne, the mountain range suddenly rises up out of the near dead-flat Wimmera plains, a stunning sight in itself, but wait till you get to the top!

The nearest regional centre to the Arapiles, is Horsham. Head west from there on the Wimmera Highway until you get to the small township of Natimuk. There’s a really good general store there for some basic last minute supplies. From there, you can’t miss the mountain range. It’s dramatic, stunning and rises up out of the Wimmera plains to dominate the landscape. There are over 2,500 different routes to climb on this mountain, which provides a massive range of options for the beginner, right through to the advanced lead climber. Even though you’re bound to find other climbers around, there’s plenty of options from which to choose. To get started, there’s a number of small, short climbs with easy road access and simple to setup top belays without having to lead climb up. These are perfect for the whole family, training the kids, or just bouldering to improve your own technique. Further in, the mountain opens up into a massive collection of climbing routes for all skill levels and abilities. There’s an abundance of multi-pitch lead climbs up challenging rock faces, chimneys and stand-alone rock pillars. For less experienced climbers, guided climbs are available from the local area. For the experts, grab yourself a route map and get climbing! The views from the top are stunning. The mountain is a stand-alone feature on the landscape, so all around you it drops down to the beautiful agricultural plains of Western Victoria as far as the eye can see. There’s way too much to do here for just one day, so plan to make a trip of it. If you want to stay onsite, you must book camping in advance via the Parks Victoria Website. The camp ground has a great international atmosphere, with people from all over the world hanging out and taking on the variety of challenging rock faces. Whilst this is an all year round location, Summer here does get really hot, so from a risk point of view just keep that in mind. If you love climbing, then this is by far the best place to do it in Australia! PACK LIST: • Tent • Sleeping Bags • Sleeping Mat • Food • Gummy Bears (because you just can’t go wrong with them) • Camping Stove • Firewood (You're not allowed to collect wood from the site.) • Water • Lanterns • Sunscreen • Insect Repellent • Clothes for hot midday and cold nights • Climbing Gear (helmet, ropes, harness, devices, shoes) • First Aid Kit • Camera Risk management in schools is an interesting and challenging problem. Firstly, there’s nothing in teachers’ training which helps them to understand the role and responsibilities of planning for and managing risk. Secondly, what actually are the risks? What could be considered a hazard or risk in the classroom, is vastly different from what could be considered a risk on the sports field, out on camp, or on an international study tour.

In years gone by, this wasn’t too much of a worry as most teachers weren’t involved with the sheer volume of additional co-curricular programs, excursions, activities and overseas trips which now form part of a normal year at school. Added to this, the focus of risk management in schools has also predominantly been on buildings, grounds, office spaces, classrooms and boarding houses and not on the specific activities which go on outside the school grounds on a daily basis. The fact is, on-site risk management is quite different from off-site risk management. However, often there’s only training available for on-site risks. This makes no sense, as schools continue to run great education programs inside and outside of the confines of the school grounds. As an experienced outdoor education professional, if I were to do a walk-through of an entire school as part of a risk assessment, then I would most likely miss several things because it’s not my specific area of expertise. The same is true when Workplace Safety Professionals attempt to evaluate risk outside of the school. Unless you’re specifically trained in excursion and activity risk, you’re bound to miss something, which can lead to injuries and incidents which could have been avoided. The only education that teachers seem to have in risk management is that at some point, they’re involved in a trip somewhere, doing something, and rather than having any actual training to be able to manage and help run the program, they’re entirely reliant on learning something about what they should be doing through osmosis. The expectation that they absorb something at some point in time, which then magically enables them to manage risk in a well-planned and professional way, is ridiculous in the extreme. Yet that’s basically what’s been the industry standard. People reference ISO31000 all the time. (This is the international standard for risk management). However, if you’ve ever had enough coffee to drink and made it all the way through the ISO, you’ll realise that it’s so broad and general that just reading this doesn’t give you any real idea about how to manage school excursion and activity risks. It does however, outline what the paperwork should look like. Sadly, osmosis and reading ISOs is a rather unreliable means through which people gain even a decent baseline understanding of risk management. It’s like letting your English teachers learn about a text for the first time as they read it in class with their students, or your maths teacher, teach themselves by reading a chapter ahead and asking the other teachers a few questions about ‘this whole algebra thing.’ Schools and teachers have a professional responsibility to manage risk wherever their educational programs take them. Whilst this is a significant concern, which the recent pandemic has focused everyone’s minds on, rather than just continuing to say it’s a concern and something should be done about it, we decided to do something about it. From our 20+ years of running school excursions, camps, co-curricular programs, sports and international tours, we decided to create structured, professional development training for teachers in risk management that’s specific to excursions and activities. Risk management is not generic and for school activities, it cannot be covered effectively by workplace health and safety risk training. When you’re dealing with students, staff, transport, activities, airports, medical concerns, mental health issues, activities and a range of educational programs, teachers need to be trained and confident in their planning and management of these specific inherent risks to ensure programs are well run and enjoyable. Nobody is ‘just a classroom teacher’ anymore. The more our school programs venture out into the real world, the more important it is to have teachers with great risk management skills. Every time teachers leave the school gates with a group, they’re responsible for the safety and well-being of that group and like the English teacher reading the text as they go, teachers regardless of subject expertise, should not be out on a trip, anywhere, doing anything and making it up as they go. This leads to disaster and at the end of the day, as educators, we want to run great programs which have well-planned safety built into them. We decided to share our experience of risk management, through online and face to face professional development. Over the years, I’ve had the best moments of my teaching career and seen the most impact, when we’ve been out on some sort of excursion or activity. From this, we want to enable all those teachers who want to improve student learning through amazing real world experiences, to be able to gain confidence and strength in their risk management skills so that every trip of which they’re part, is a memorable one for their students for all the right reasons. OK! Before you fall asleep with the thought of two days of risk management training, hear me out!

What are the most exciting things you do in education? It probably has nothing to do with sitting in a classroom and completing worksheets. Each year, that puts countless people to sleep. Education needs to be dynamic, exciting and engaging to equip students with the skills they need for life. However, to run really cool programs like this, we usually have to step outside the school gates and engage with the real world. Only problem is that when we do this, there’s a whole stack of inherent risks with which we’re suddenly confronted. Everything from your usual stack of peanut allergies, to your bus strangely catching on fire, which to be clear was not actually my fault. The randomness and richness of the world outside the school gates is the most amazing place in which to learn, but if we’re not trained and equipped to plan for and manage risks in this environment, then we’re putting ourselves and our students at risk. At this point we have three options: Option 1. Don’t go! It’s all too hard! School’s not about the real world anyway. If you take this option, you probably should have become an accountant or a public servant, perhaps both. Complete risk aversion is pointless and damaging and should be avoided. Option 2. Just do it! Grab your bags, kids and let’s go! If you take this option, which unfortunately, I’ve seen many teachers do, then you’re setting yourself up for some major problems. Anything can and does go wrong in these situations where well-intentioned teachers don’t take the time to plan, prepare for and run their programs carefully. Option 3. Have a structured, well-planned approach for all of your programs which documents the steps you need to take to ensure your group is well managed and the focus is on great experiential education outcomes for students, with robust systems in place for contingencies to support this. For me, the only option when running any excursion, camp, sport or activity is Option 3. However, most schools are operating somewhere in between Option 1, 2 and 3 with many teachers confused about their role and responsibilities when planning and running any programs. Even experienced staff can struggle with this. You must put the time, energy and effort into building a well-formed plan no matter what the activity is. It could be just going down the road to visit the local court. It could be a year level camp, or an overseas trip. Whatever the case is, you need to ensure you’ve planned for normal operations and contingencies if something doesn’t go to plan, which invariably will be the case. One trip I was on, I received a phone call to say that one of the 5th Grade students had been taken to hospital with a fish hook in his arm! I was pretty surprised by this, since there was no fishing on the program, yet here we were with fish hook in the arm, right next to a vein. Risk Management Training prepares you for weird random stuff like this and how to respond quickly and effectively no matter what the context. With a non-delegable duty of care, you also can’t outsource your risk management to another organisation, even if they suggested you can. It just doesn’t work that way. Instead, you and your school are ultimately responsible for the duty of care over your students for any trips you’re on. “But they didn’t tell us that at uni!” I hear you say! True, unis don’t actually equip teachers with most of the skills they need with which to teach, but that’s another matter. At the end of the day, if you’re running any sort of excursion, camp, sport, overseas trip or any other sort of school activity which requires you to produce a risk assessment, you need to be trained in risk management. It’s no good just to copy and paste what the last untrained person produced and put your name to it. That’s a dangerous precedence which will come back to bite you. Risk management training isn’t about putting you to sleep for two days. It’s about giving you clarity and confidence through practical experienced-based training on how to run effective and safe programs. Get in touch with us today to see how you can build this training in to your professional development schedule to ensure you’re running the best programs possible for your students. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|

Copyright Xcursion Pty Ltd 2015-2023

RSS Feed

RSS Feed